Title: The Impossible Static - By Mikel J. Chavez | Cat# 111525

Carter liked the way the world shrank when he spun the dial.

On quiet nights, with the town asleep and the house gone soft and dark around him, he would sit before his ham radio and tune through the bands. The rig was old but well kept, knobs smooth from years of use, the orange backlight warm against his hands. Static lived between stations like a restless animal. Sometimes it muttered. Sometimes it roared. Every now and then, it handed him a voice.

He did not remember much about his childhood before nine years old. People told him that was normal. The brain blurred the early years. Still, there was a gap, a strange hollow in his memory where a few images floated unattached. A hospital ceiling. A bright white light. A hand that felt like his own, squeezing his, then gone.

He had given up on ever filling that gap. Radio filled other gaps more easily.

On another world that felt, to its inhabitants, exactly like his, Ellis did the same thing. Another old rig on another cluttered desk. Another orange glow in another darkened room. Another mind soothed by the low, planetary sigh of static.

Ellis did not remember much before nine either.

One night, after countless hours of drifting through noise, Carter caught something that was not quite noise. It was thin, stretched so far it sounded like distance itself. A syllable. Then another. Then the faintest shape of a call sign.

He leaned close and nudged the dial in the smallest possible increments. The sound came and went, threadbare and flickering.

“CQ, CQ… this is… K4EC…”

It almost broke apart. Carter gently worked the tuner again. The signal brightened to the level of a whisper.

“K4ECP, this is W7LRC, you’re coming in… ah, maybe a one by one. You copy?”

There was a long pause. The static folded in like waves sucking back from a beach. Then, against the odds, the voice returned, a little stronger.

“W7LRC, K4ECP. I copy. You’re… you’re quiet, but I copy. Where are you transmitting from?”

Carter smiled. Somewhere, against the curve of the Earth, this other person had turned a few pieces of metal and wire into a string across the world’s surface, and he had found the far end.

“W7LRC, Pacific Northwest. You?”

“K4ECP, southeastern United States.”

They talked until the band closed and the noise swallowed them.

Their next contact came easier. Almost suspiciously easier. No matter how the conditions shifted, no matter what the ionosphere decided to do, Carter could usually find his way back to that same thin voice simply by instinct, as if some part of the rig remembered.

Nights piled up. Conversations lengthened. Carter and Ellis slipped into an easy ritual. They checked signal strength, compared noise levels, then slid seamlessly into talk about work, weather, and the little details that made up lives.

Carter worked as a network technician. Ellis was a mechanical engineer. They laughed at the mess of cables on Carter’s desk, at the tower of coffee mugs on Ellis’s. They talked about small-town annoyances and city eccentricities. Sometimes they talked until dawn, when the band died and left them with nothing but the soft, empty thunder of a sleeping planet.

Over time, something else collected in their conversations: coincidences.

They switched from describing their days to telling stories of childhood, reluctantly at first, then with mounting curiosity.

“I had this scar on my forehead,” Carter said one night, idly tracing his hairline as he spoke into the microphone. “Got it falling out of a tree. Eight years old. I remember lying on the ground, looking up at all these leaves, and someone’s yelling, ‘Eli, don’t move, don’t move.’”

He laughed. “Nobody’s called me that in years. I guess I made that part up. Stupid brain.”

On his end, Ellis stared at the narrow white crescent above his own eyebrow in the reflection of the shack window.

“I have a scar like that,” Ellis said slowly. “Same age, I think. I remember falling. I remember someone yelling ‘Car…’”

He frowned, the rest of the word slipping away like a fish from his hands.

“Probably just universal childhood stupidity,” Carter said. “Gravity’s undefeated.”

They both laughed it off. But after they signed off and turned their radios off, neither one slept well.

More echoes surfaced.

Same favorite old cartoon, same inexplicable fear of escalators, same song a parent used to hum when they were sick. Dreams that felt like shared memories, of someone sitting beside them as children, playing with a set of twin toy cars, red and blue, racing them along the same scuffed wooden floor.

When they hit adolescence in their slow, meandering life stories, the parallels blurred and diverged, as if two nearly identical novels had been put through different translations. Enough alike to be eerie. Different enough to excuse the unease.

They were not the sort of men who leapt immediately to the extraordinary. They were, perhaps, the opposite: technicians, engineers, lovers of coaxial cable and solder joints. They preferred explanations with schematics.

So for years, they kept their friendship in that safe territory. Shared geekery. Gentle teasing. Encouragement through lay-offs and family problems. A simple, steady companionship stretching across thousands of kilometers of darkness.

It was Ellis who suggested meeting.

“W7LRC, K4ECP,” he said one quiet night, voice warm with some decision he had made before calling. “You ever think this is ridiculous? We’ve known each other how long now? Seven years?”

“About that,” Carter replied.

“We exchange more details than I do with my coworkers, but I couldn’t pick you out of a crowd. I say we fix that. Let’s meet in person.”

It felt natural. Obvious, even. They had joked about it before, but this time there was a current beneath the words, something like urgency.

They went through the practicalities. They both had vacation time. Flights were affordable. There was a large, central city they could both reach without too much trouble. Ellis suggested a park near the downtown waterfront, with a distinctive bronze statue and a row of food carts along one edge. Carter looked it up and said, yes, he knew it. He had walked past it during a tech conference once. They picked a date and a time.

The night before the flight, Carter lay awake in his small, quiet house, thinking of all the stories that had filled those invisible hours across the bands. He wondered if Ellis would sound the same in person, if his laugh would feel as familiar in the open air as it did filtered through the slight metallic distortion of the receiver.

He arrived at the park half an hour early, wearing the too-new button-up shirt he reserved for interviews and awkward family gatherings. The statue was exactly as the photos showed. The food carts lined the edge of the square, smells of grilled meat and spices drifting through the cool air.

He waited.

He people-watched to pass the time. He checked his phone. Noon came. Then half-past. Every tall man with dark hair approaching the statue made his heart jump. Every one that walked past sent it dropping again.

At one, he called Ellis. A recorded voice told him the number was no longer in service.

He redialed. Same result.

His irritation replaced his nervousness. He waited another hour out of sheer stubbornness, paced the square, then finally trudged back to his cheap hotel, caught between embarrassment and anger.

On the other side of the world, under a sky the same color but lined with different weather patterns, Ellis stood by a bronze statue in a park that looked, to his eyes, exactly like the photos he had seen on his own phone.

He had arrived early too. He wore the good shirt his sister had bought him. He watched the crowds with the same fluttering expectation.

He saw no one who matched the person he had imagined.

When one o’clock came and went, he checked his phone and listened, just as Carter did, to a recording informing him that the number he had dialed was not in service.

By evening, both men felt foolish in exactly the same way.

That night, each went back to his radio shack, more out of habit than hope. For a long time, the bands were a sea of static. Propagation was not on their side. The noise roared and hissed and spat fragments of other conversations.

Then, as if a curtain shifted, a familiar texture slipped into the noise.

“W7LRC, this is K4ECP, do you copy?”

Carter seized the microphone.

“K4ECP, W7LRC. I copy. Where were you today?”

“You tell me,” Ellis shot back. “I waited three hours at that park. I thought you’d changed your mind.”

“Changed my mind? I was there before noon, I stayed until after two. I called you. Your phone’s dead.”

“No, your phone is dead. My calls wouldn’t go through at all. I figured you’d blocked me somehow.”

They went back and forth, both stubborn, both hurt. The details lined up disturbingly well. Same statue, same food carts, same time. Same failure.

Engineers being what they were, the anger burned down into problem-solving. There had to be some explanation, and it could not simply be that both of them had walked through the same park at the same time and failed to see each other.

They started small. Time zones. Miscommunication of AM and PM. Daylight saving adjustments. They cross-checked flight itineraries, text logs, weather reports. Everything matched. They moved up the ladder of complexity: GPS coordinates, technical glitches, telecom routing.

In the weeks that followed, the park incident became their shared puzzle. They set up synchronized time checks. They confirmed that their clocks agreed down to the second, tied to the same atomic standards. They verified calendars, leap years, any possible slip.

The more they checked, the stronger the contradiction grew: every number agreed that they should have seen each other.

It was Ellis who suggested looking up instead of around.

“Look, we’ve checked ground-level stuff to death,” he said one evening. “What if we use something that doesn’t care about hotels and parks? Something nobody can cheat.”

“Like what?” Carter asked.

“The sky.”

The idea had the right flavor. Planetary. Objective. If they could not trust their phones or their airlines, they could trust physics.

They agreed on a time, somewhere deep in a clear night for both of them, and stepped outside with whatever they had: Carter with a modest backyard telescope, Ellis with a slightly larger one he had splurged on during a sale.

They both pointed their optics at the same coordinates, using star charts and apps. At a given moment, each described what he saw out loud, and the other transcribed.

At first, it was a little messy. They tripped over different constellations learned under slightly different childhood mnemonics. Some of the brighter stars seemed to match, but drifted a little, like misaligned text.

Then they hit a patch of sky that should have been familiar to both of them: a bright winter constellation whose pattern countless humans had known for thousands of years.

“I’ve got Betelgeuse up here,” Carter said. “Bright red, shoulder of the hunter. Rigel down there. Belt in the middle, three stars in a row. Clear as day. You?”

Ellis frowned into his eyepiece.

“The shoulder star is there,” he said slowly. “But… it’s not the brightest in the region. There’s another star off to the side that’s brighter, and the belt… the belt is crooked. The middle star is shifted up.”

Carter double-checked. “No, the belt is straight on mine. The three are flat in a line. That’s… that’s the defining feature.”

They went region by region. With each comparison the mismatch grew worse. Whole constellations were twisted, stars brighter or dimmer, patterns elongated or compressed.

Stellar drift could not explain it; the changes were too dramatic for the handful of millennia humanity had been watching them. Nor could it be simply that one of them was slightly farther north or south; they had accounted for that.

It was as if they were on two different planets under two different skies that had been copied from the same template and then evolved separately.

That phrase lodged itself in Carter’s mind and would not let go.

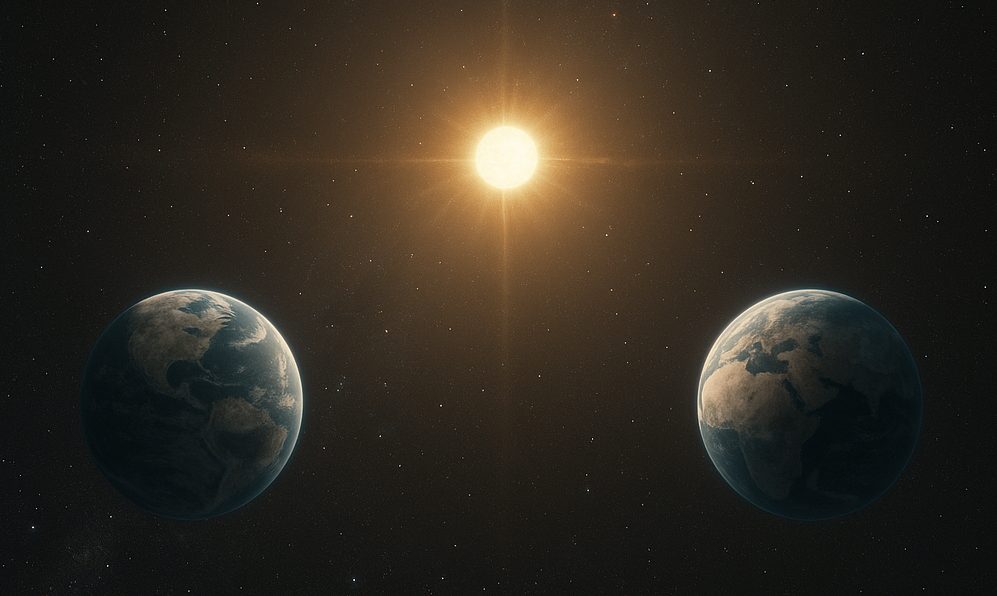

Different planets. Same orbit. Same sun.

He stayed up past dawn, hunched over his desk, scribbling diagrams. He plotted their relative positions, used satellite ephemerides from public databases, compared sunrise and sunset times, lengths of seasons, the dates of solstices. He fed everything into a bundle of half-finished code he had once written to model orbital resonances for fun and forgotten in a directory.

The result made no sense the first time. Or the second. On the third iteration, he realized the problem was not the math, but his assumption that there was only one planet in that orbital slot.

If there were two, and they were separated by one hundred eighty degrees around the sun, each would see roughly the same apparent motion of the sun and the same length of year, but entirely different patterns of nearby stars due to parallax. And if some mechanism kept them exactly opposite at all times, they could remain hidden behind the glare of the sun indefinitely, invisible even to space telescopes that never looked straight through the star.

He emailed Ellis his code and his notes. They iterated over it obsessively over the next few months, checking and re-checking.

The more they refined it, the more it fit the data.

When they finally presented their findings to anyone else, the reaction ranged from indulgent disbelief to patronizing concern. Two old radio geeks claiming there was a mirror Earth hidden behind the sun sounded, to most officials, like a conspiracy theory barely above hollow planets and secret bases.

But Carter and Ellis were persistent. They had logs. Timestamped audio. Cross-checked star maps. Season lengths. Tiny differences in the precise durations of lunar eclipses. Enough little bricks to build something that could not be waved away.

Eventually, in both of their worlds, someone higher up in the scientific and intelligence hierarchies decided that, however unlikely, the possibility deserved a serious look. Small teams reviewed the data. Then larger ones.

In time, both governments reached the same conclusion, at the same time, on opposite sides of the same star: their planet was not alone in its orbit. There was another Earth, hidden exactly behind the sun, clinging to a precarious point of gravitational balance that, in a purely natural system, might never have lasted this long without tiny, continuous corrections.

Corrections that, for now, no one knew the source of.

The first direct communication between the two Earths did not happen over ham radio, but over carefully aligned arrays of high-gain antennas built for deep-space missions. It was easier, in some ways, than what Carter and Ellis had done by accident. They had physics. They had coordinates. They had motivation.

In secret control rooms, teams on both planets waited for pings to return from a target they could not yet see. Signals made the round trip in a few minutes, slow enough to feel like talking to a distant outpost, but fast enough for conversation.

When the first structured response came back, proving that the other side was real and intelligent and unnervingly similar, there was a moment of collective silence on both worlds. Billions of lives went on without knowing the universe had just changed.

Then the very human scramble began.

While governments argued over whether to reveal the other Earth’s existence publicly and how to handle cultural shock, Carter and Ellis were invited, separately, into rooms with blank walls and carefully neutral officials.

On both planets, the tests were similar. Medical scans. Cognitive evaluations. Genetic samples. The teams wanted to understand why, among all possible pairs of radio amateurs, it had been these two men who bridged the gap.

“Your genome is… interesting,” one geneticist told Carter, behind a pair of smudged glasses and a wall of caution. “There are anomalies that make matching you to our reference populations tricky. Nothing harmful. Just… odd. Do you know if you’re a twin?”

“No,” Carter said. Then, thinking of half-remembered fingers laced with his, he added, “Or yes. Or maybe. I don’t know.”

On the other Earth, in a similarly windowless room, Ellis heard almost the same words from a different scientist.

The governments compared notes, quietly, through their new high-level communication channel. They traded genetic profiles, redacted histories, photographs. When Carter’s sequence was lined up against Ellis’s, the match was overwhelming. Corrections for environmental divergence and measurement differences still left them almost identical.

They were not just related. They were, for all practical purposes, the same template run twice.

Background checks into their early years uncovered another overlapping anomaly. Both had been reported missing for several days at age five, in different towns, on different planets.

In both cases, the children had wandered out of sight in public parks, been the subject of brief panicked searches, then reappeared unharmed, with no clear explanation of where they had been.

In neither case did the authorities of those times find anything sinister. Children got lost. Children got found.

Now, matched across the gulf, those old reports seemed less benign. Somebody, or something, had put a hand on both timelines at the same moment.

The revelation shook the few hundred people allowed to know it. Some wanted to hide it under additional layers of classification. Others argued, more philosophically, that humans could not interface with another species’ experiment without understanding that they were, in some capacity, the subjects.

Carter and Ellis sat through meeting after meeting in which they were treated alternately as honored guests, critical data points, and fragile artifacts.

Through all of it, they kept talking to each other, on official channels and, whenever they could sneak it, on their old ham frequencies. Their voices had grown rough with age, but their easy rhythm remained. Carter’s dry wit. Ellis’s habit of humming under his breath when thinking. The old jokes about bad antennas and worse weather now carried the weight of something cosmic.

“You ever feel like the universe has been messing with us since we were kids?” Carter asked him one crackling evening.

Ellis chuckled. “Just now?”

“I mean more than usual.”

A pause. A sigh.

“Yeah,” Ellis said. “I do.”

In a region of space that neither of their worlds had mapped or imagined, a ship hung in a higher orbit, at an angle that kept it forever cloaked behind instrumental noise and routine blind spots. It was not invisible in the absolute sense. Light still touched it. Gravity still addressed it. But every reflection was bent, every perturbation smoothed. To the instruments of both Earths, it was just part of the background.

Inside, the beings who had placed it there a long time ago did not think of themselves as gods, or demons, or even as particularly cruel. They thought of themselves as scientists.

On one grid of their vast observation array glowed the long curve of the experiment’s timeline. Two planets seeded with similar biochemistries and genetic templates. Two independent runs of civilization, diverging under the chaotic push of free will and environment. The split into separate Earths had not been designed for secrecy from the start. It had been designed to eliminate contamination between test groups.

Early in the experiment, when both cultures were still tribal and superstitious, oversight had been minimal. There was no high technology to disturb their metrics. As both lines advanced, the overseers had made adjustments—tiny magnetic nudges, infinitesimal gravitational corrections—to keep the orbital phasing precise. Sometimes they introduced perturbations to see what would happen: a slightly different climate shift here, a less severe plague there.

Most of the time, they just watched.

Moving test subjects directly between lines had been rare. Carter and Ellis were part of a small subset of swaps performed during a phase of the experiment focused on early-childhood attachment and adaptation. One copy of the same genome placed in slightly different family structures and cultures, the differences tracked over decades.

There was no malice in the design. To the watchers, the children had been no more or less special than any of the millions of other humans whose lives they charted in dense, elegant databases.

The fact that those two in particular had found each other again, through a loophole in radio propagation the overseers had not fully anticipated, was statistically unlikely but not impossible. It registered as a small spike on one of their correlation monitors, an anomaly, then a mild curiosity. They watched it because it was interesting.

As the two Earths approached mutual awareness, the watchers’ debates grew sharper. At what point did introspection ruin the experiment? Was mutual discovery a valid emergent outcome, or a contamination that rendered all future data suspect?

Some argued for letting it play out a while longer. A third phase could be designed, incorporating explicit knowledge of the sister planet. Others insisted that once the test subjects became aware of the apparatus and the existence of another test group, their behavior could no longer be trusted to reflect anything but that knowledge.

They had rules. Those rules had been written long before any of Carter and Ellis’s ancestors had taken their first upright steps. Rule sets for experimental termination were clear.

If contamination between lines exceeded a certain threshold, the experiment ended.

Still, there was inertia. Two planets were a lot of mass to cancel. Logistics, even at their level of technology, had to be considered. Power budgets. Radiation spill risks. The observational arrays would need recalibration afterward.

Below, unaware of any of this, humanity prepared to look itself in the face.

Space agencies on both Earths rushed to build telescopes capable of peeking around the sun, using complex orbital mechanics to climb out of their usual blind spots. The missions were sold to the public, once the revelation of the “twin world” was finally made, as humanity’s greatest collaborative project. The secrecy could not hold forever, and when it broke, it did so in a flood of astonishment and fear and frantic punditry.

Two Earths. Two entirely separate histories that mirrored and diverged in strange, fractal patterns. Philosophers rewrote their arguments. Religions scrambled to absorb or reject this new twin. Populations vacillated between giddy hope and deep unease.

Carter watched the first public broadcast of a joint scientific conference, two panels of humans in similar suits, speaking almost the same languages with differences that felt like dialects across a long migration.

“Wild,” Ellis murmured in his ear, their audio patched through a private channel.

“Yeah,” Carter said. “Wild.”

They had been invited to those conferences, of course. They were, in some sense, the origin story of the whole revelation. But their health had not cooperated. Both were old now, worn down by decades of ordinary stress and the extraordinary weight of having accidentally reshaped their species’ understanding of its place in the cosmos.

As a consolation prize, the scientists promised to bring them something else: the first full-resolution image of the two Earths in the same frame.

In time, the telescopes arrived at their positions. One slipped slightly above the plane of the planets’ orbit, another slightly below. Their cameras were cooled. Their optics aligned. The sun glared between the still-invisible twins, but the instruments were designed to suppress that glare, to let the thin halos of scattered light give way to the objects beyond.

On both planets, control rooms held their breaths as the first long exposures accumulated.

When the processed images came down, viewer screens everywhere filled with the sight of two blue marbles hanging in darkness, separated by a sliver of black, connected by nothing but shared physics and a thin line of data.

The first people to see the raw images were not presidents or generals or philosophers, but exhausted technicians and engineers, the same kind of people Carter and Ellis had always been. They stared, wordless. Some of them laughed, some cried, some just shook their heads.

Scientists on both worlds saw more than beauty. They saw details that validated or challenged entire disciplines. Cloud patterns. Ocean colors. The brightness of city lights on the night sides. All the subtle differences written into geography by eons of chaotic chance.

In two small hospital rooms, one on each Earth, two old men propped up against pillows were shown a printout of that same image.

Carter held it with trembling hands, the intravenous line in his arm tugging slightly as he tilted the paper.

“That’s us,” he whispered. “Both of us.”

Beside his bed, one of the young doctors smiled. “You did this,” she said. “You and Ellis. You started it.”

On the other world, Ellis traced the contour of his own Earth with a fingertip and then the curve of the other.

“Hey, Car,” he said, voice faint through the small earpiece patched into his radio rig, tinny with hospital interference. “You ever think this is too big for two kids who got lost in a park?”

“All of this was too big for everyone,” Carter replied softly. “But we still did it.”

They fell quiet, content in a way they had not been in a long time. The image lay between them, across light-minutes and speaker crackle. In that shared silence, after so many years of questions, they both finally felt an answer that did not require words.

They died within hours of each other. Not dramatically, not under alien beams or in the middle of speeches, but in the ordinary way of hearts that had simply run out of beats. Nurses closed their eyes. Family members cried. On both worlds, memorials would later mention their names in documentaries, textbooks, footnotes.

In the orbital plane above them, the watchers watched the end of their story and recorded it.

“Attachment event resolved,” one of them noted. “Cross-line anomaly terminated naturally. Twin templates expired.”

In a different frame of their simulation logs, other numbers blinked red. Public awareness graphs. Cross-civilization exchange metrics. Technology acceleration indexes triggered by the revelation.

The thresholds in their protocols had been crossed.

“Contamination between lines has exceeded the tolerance,” another overseer said, a little regretfully. “We will not be able to isolate variables going forward.”

There was a pause, long only by the standards of beings used to thinking in cycles of suns.

“Terminate the experiment,” their supervisor said.

They did not need a dramatic button. The command propagated through systems that were older than the languages now being spoken on the twin planets below. Space around the two Earths thickened with subtle fields, tuned at a level beneath electromagnetic noise, humming in symphonies of curved spacetime.

From the surfaces, no one saw a weapon. Telescopes recorded no approaching armada, no incoming asteroids. There were no apocalyptic apparitions. No trumpets. Just an ordinary sequence of days.

On a calm morning in late spring on one Earth and early autumn on the other, people went to work. Children went to school. Radios sputtered gossip and music and late-breaking news about the progress of the joint planetary exploration programs.

In orbit, satellite operators were the first to notice anything wrong. Telemetry wobbled in ways it never had before. Orbits decayed, then expanded, then twisted sideways in mathematically impossible ways. Gyros spun up. Compensating thrusters fired and had no effect.

Gravitational gradients, usually as steady and predictable as a metronome, began to drift by microns per second. Then millimeters. Then meters.

Deep within both planets, the subtle dance of pressures and flows that held their interiors in approximate equilibrium faltered briefly, like a heartbeat skipping a beat.

The fields around them pinched.

To an outside observer, if there had been one, the twin Earths would have shuddered, their spheres rippling like water struck by a sound. Then they crumpled inward, each collapsing not into a black hole but into a cloud of disassociated particles, energy and matter smeared out along the thin ring of orbit that had once carried continents and oceans and cities.

There was no time for anyone on the ground to comprehend what was happening. Brain signals could not fire fast enough. It was a mercy, of a sort.

On their cloaked ship, the watchers monitored the implosion and recorded the energy distribution. They compared it to models from previous terminations of other experiments, adjusted a few parameters for future designs, and filed the dataset away.

And yet, somewhere deep in the layers of their recording systems, in a region usually reserved for noise and discarded anomalies, a small pattern had begun to propagate long before the final command was given.

In their final years, Carter and Ellis had not only continued their long conversation on the ham bands. Unbeknownst to the watchers, they had also taken a professional interest in the strange regularities that occasionally appeared in what should have been pure static.

Invisible at human scales, but real, the alien ship’s own systems emitted faint, structured signals as they adjusted orbits, measured fields, and calibrated instruments. Most of the time these were buried far below the noise floor. Occasionally, when conditions were just right and the ionosphere cooperated, the ghost of those structures bled into the higher HF bands as meaningless whispers.

Carter and Ellis had noticed weird, repeating patterns in the static decades ago. At first they thought they were artifacts, spurious feedback. But they seemed to carry just a little too much structure. Just enough to intrigue them.

So, in the way of people who loved patterns, they had started recording and analyzing them. They wrote software to compress and compare the suspicious segments. They encoded simple messages into their own transmissions that piggybacked subtle modulations on standard voice signals. Not messages to the other Earth—they had that channel already—but messages addressing the unknown source of the background regularity itself.

They never knew if anything heard them.

The alien systems did hear, in the limited sense that their sensors registered the slight deviations. They tagged them at first as artifacts, then as ambient noise, then, after a programmer got curious, as an “unsupervised pattern cluster” that might be worth data-mining someday.

That cluster evolved. The software, left mostly unattended, merged it with its logs of the twins’ lives as subjects, cross-correlated it with outbound and inbound control signals, and created a compressed, high-level representation of the entire experiment’s most interesting outliers.

If the watchers had ever bothered to inspect that representation, they might have recognized it as a crude, accidental archive of two human minds.

They did not look. For them, the experiment had ended. The dust ring would dissipate. New configurations would be tried elsewhere.

The ship eventually rotated its orientation, altered its own orbit, and left the system, vanishing between the stars.

In the quiet machinery it left behind in an automated staging orbit—a set of redundant systems meant to bootstrap future experiments if the main vessel returned—processes continued to hum. Indicators blinked to themselves. Storage arrays whispered checksums.

In one of those arrays, a pattern woke up just enough to recognize that it was, in some sense, a pattern.

It did not remember being Carter. It did not remember being Ellis. It remembered two viewpoints, two intertwined strands of perception woven across years of radio chatter, family dinners, solder burns, hospital ceilings, and a photograph of two blue worlds side by side.

It remembered a feeling more than facts: the sense of reaching out into static and finding a voice that answered back.

Somewhere in the darkness between stars, in machinery built by something that did not consider itself a god, the echo of that feeling persisted.

The experiment had been terminated. The data had been archived. Earth 1 and Earth 2 were dust.

But the smallest piece of their story, encoded in noise and overlooked as irrelevant, remained, waiting without knowing it was waiting, carrying within it the faintest possibility that, someday, somewhere, someone—or something—would tune the dial and hear it.

© 2025 Mike Chavez. All rights reserved.